Irish Ireland

Irish Ireland — a generic term for the forms of cultural nationalism that took shape during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Ireland. In part this was a turning away from politics after the heightened drama of the Parnell period. In part it was a reaching for deeper cultural roots after a half-century of extraordinary social change – famine, evictions, emigration on a massive scale.

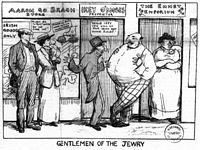

The Victorian English attitude to Ireland also played its part. The magazine Punch, for instance, regularly portrayed Irish people as ape-like creatures, both physically and mentally inferior. Irish-Ireland was an attempt to "create a more positive image" and "enhance self-esteem in the Irish themselves".

The period 1890-1910 saw a revival of interest in all things "Gaelic" – language, sports, music, dancing. Sometimes this tended to the dreamy side, as in the early "Celtic" poetry of Yeats. Sometimes it was plain absurd, as in the invention of "Irish" kilts. Irish-Irelanders argued that political separation was meaningless unless underscored by cultural distinction. The movement was an attempt to de-anglicize Irish society, to "enable" Irish men and women to "grow up Irish".

It was in this spirit that the lower middle classes, predominantly urban, attended their Gaelic League branch, earnestly mouthing Father O'Growney's Simple Lessons in Irish. The Kellys and Murphys amongst them rediscovered the "O" in their surnames, re-becoming the O'Kellys and O'Murphys. Sometimes they went so far as to spell their names in Irish (Ó Ceallaigh, Ó Murchadha) – to the bewilderment of the police and courts who refused to recognize such novelties. They wore Irish poplin and Irish tweed, and ate Irish-manufactured biscuits with their cocoa. They read Arthur Griffith's Sinn Féin newspaper. On Saturday afternoons the men played hurling at the local Gaelic Athletic Association field. On Sundays they marched in a pipe or a flute band, swishing down the thoroughfares in saffron kilts. The girls amongst them yearned for a crossroads at which to try out their slip-jig steps.

Its notion of a future Ireland was at heart atavistic: a contented rural cottage-nation, self-sufficient in creameries and lace – and lauded by the urban lower middle class, safe in their clerkships and post office jobs.

Its notion of a future Ireland was at heart atavistic: a contented rural cottage-nation, self-sufficient in creameries and lace – and lauded by the urban lower middle class, safe in their clerkships and post office jobs.

Initially Irish Ireland turned away from politics, from the jobbery and dealery of the Irish Parliamentary Party. But gradually, in the legends and myths of the Gaelic past, it found a new paradigm of politics, one that seemed noble and clean. The beardless hero Cú Chulainn and the warrior band of Fionn mac Cumhaill pointed to deeds that were bold and direct. They were selfless to the point of sacrifice.

The Gaelic Athletic Association annual of 1907 sums up this ideal of the Gael:

In 1911 the GAA President proclaimed,

Amongst those who fought in the Easter Rising were hard-headed Fenians and hard-headed socialists. But the great many, in their hearts, were Irish-Irelanders.

Links

UCC Multitext: Irish IrelandUCC Multitext: Nationality, Nation, Nationalism

UCC Multitext: Anglicisation and de-Anglicisation

Douglas Hyde, The Necessity for De-Anlicising Ireland, 1892

DP Moran, The Gaelic Revival, 1899