The Dublin Lock-out, 1913

A major industrial dispute in Dublin that lasted from August 1913 to January 1914. At its height, it involved over 300 businesses and 20,000 workers – either on strike or "locked out" by their employers. These workers, whose families amounted to 100,000 souls, represented the poorest third of Dublin's population. It was the most severe industrial dispute in Irish history, marked by violent suppression and enduring bitterness. Central to the dispute was the workers' right to organize.

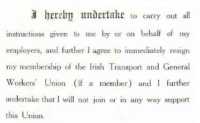

Larkin had organized the workers. The plutocrat, William Martin Murphy – newspaper magnate, tramway boss, international investor, prominent Irish nationalist and former MP – organized the employers. In August 1913 his Dublin Employers Federation announced that no one – man, woman or child – might work in Dublin unless first he pledged to repudiate Larkin's union. The workers refused to pledge. Whereupon they were locked out of work.

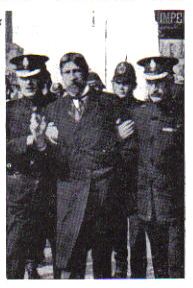

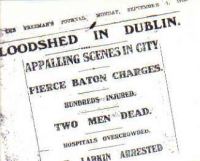

Thus began the "Big Strike" or the "Great Strike" or the "Great Lock-Out", as it was called. The workers' rallies were suppressed, the leaders arrested for sedition. The people demonstrated in response: they were baton-charged by the police. One striker was shot dead. Hospitals were overcrowded with wounded and bewildered, the prisons with the able-bodied. The employers resorted to imported labour from England and other parts of Ireland, often forming armed gangs of "blacklegs". These men in turn were stoned and cudgelled by the workers. Dublin came to an economic standstill. Even household coal might not be delivered, save with an armed police escort.

The Irish Parliamentary Party, monolithic in Irish affairs, set its many faces against the workers. Dublin Castle, seat of British administration, ranged its police, constabulary and military against them. Catholic authorities preached upon the workers' damnation. Only some few Protestant pastors, some very few artists and intellectuals, and the more canny guard of militant republicanism supported them. And the Fianna boys and girls under Constance Markievicz.

After the first whirlwind weeks, what furniture there was had been pawned from the tenement homes; the father's suit joined regiments of others in the crowded pawn office: real need and immediate hunger set in. William Martin Murphy took the opportunity to remind the workers that whatever happened, he would still have his "three square meals a day". The workers must necessarily starve.

Children were most at risk. Sympathizers in the suffrage movement in England formed a scheme to take the children to homes there, where at least food and warmth and some comfort might be promised. This scheme provoked the ire of the Catholic Hierarchy, which feared for the moral well-being of Irish innocents in English homes. The Church Militant, in its usual guise in Ireland of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, arranged howling middle-class mobs at the docks and railway stations to thwart the children's departure. The women accompanying the children were arrested for kidnapping. These same voices had been silent hitherto on the children's hunger.

Foodships began to arrive from trades unionists and other sympathizers in Britain. The nationalist Sinn Féin party, fabulously, opposed these shipments as a nefarious plot to advance British imports over Irish produce. In Liberty Hall, the union's headquarters, soup kitchens were set up. On Christmas Day, in Croydon Park, the recreational ground of the union, five thousand children received their first square meal in months. But the poorest third of a city's population could not survive on goodwill. It was concerted action by brother trades unionists in Britain that was required, and which, in the end, was not forthcoming. The British dockers must refuse to handle blacked Irish exports, else the employers could continue uninterrupted with their "three square meals a day". The Irish cargo was handled. The Irish workers were doomed. In January 1914 they began their gradual return to work.

What had dismayed the British union bosses was the sheer populism of Larkin's strike. They existed in a more settled industrial climate and had, or could have had, no real knowledge of conditions in Dublin. At a specially convened conference in December 1913, the British Trade Union Congress disowned Larkin. This climb-down determined Connolly's republicanism. During the Lock-out he had helped set up the Irish Citizen Army as a defence for picketing workers against police attacks. He would distil and galvanize that army now, in the belief that only a truly independent Ireland could advance the cause of Irish workers.

Links

UCC Multitext: Dublin, 1913 – Strike and LockoutWikipedia: Dublin Lock-out

History Ireland: Dublin 1913 Lockout

James Connolly: The Dublin Lock-out and its Sequel from the Workers' Republic, 29 May 1915.

Dora Montefiore: "Experiences in Dublin, 1913"