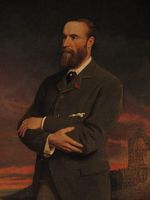

Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell — the "uncrowned king of Ireland", pre-eminent in Irish politics from the late 1870s when he became leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party pursuing Home Rule at the Westminster Parliament, until his precipitate downfall in 1890.

Gladstone called him "an intellectual phenomenon". Asquith described him as "one of the three or four greatest men of the nineteenth century". To Patrick Pearse he was "a flame that seared, a sword that stabbed".

Background — Parnell was by no means a usual Irish nationalist. He was a Protestant, of English settler descent. He was a landowner, and a landlord. He was educated in England, spoke with an English accent, and possessed the aloof manner of the English establishment. His parents separated when he was six, and the story is told of an unhappy youth in English boarding schools. His mother was American.

Yeats honoured him as a "proud" man:

No prouder trod the ground,

And a proud man's a lovely man,

So pass the bottle round.

To British public opinion this pride was incomprehensible:

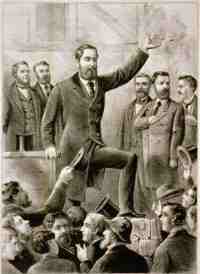

Parliament — Parnell was first returned to Westminster in 1875, as a member of the Home Rule League, a loose affiliation of moderate Irish MPs. Within two years he had seized control of the League, transforming it into a disciplined and focused political force, the Irish Parliamentary Party – one of the earliest modern party machines. His immediate aim was Home Rule, i.e. legislative separation from Britain. His strategy was obstruction. The Irish had not votes enough to repeal the Union with Britain, but they had sufficient to obstruct the process of government – not only of Ireland, but of Britain too, and of the entire Empire. Parliament held little glamour for Parnell. The long-established forms and etiquette were means to exploit, rather than procedures to obey. Such tactics outraged British public opinion: he was regularly denounced as a "barbarian" in the Press. Parnell's obstructionism and "dictatorial" discipline made him the bugbear of British politics; his daring and hauteur had him the darling of Irish nationalists.

Beyond Parliament, he had contacts with the Fenians (he was reportedly "tested" to membership in 1882). In a clear nod to Fenian republicanism he declared in 1885:

These were the years of the Land War in Ireland: agrarian unrest was widespread. Parnell alone, it seemed, could check the disorder: implicit in his checking disorder was the threat of his unleashing more. His speeches could set entire counties aflame. The British authorities imprisoned him for sedition: outrages in the country forced his release. The London Times accused him of terrorism, and, in a notorious case, was found in court to have slandered him.

He was "the Chief", the "uncrowned King".

Breakthrough — Though always a minority in Westminster, Parnell's disciplined bloc came to dominate British politics throughout the 1880s, making and unmaking governments, both Liberal and Conservative. But the breakthrough for Home Rule came with the 1885 election: Parnell had persuaded Gladstone, leader of the Liberal Party (the "Grand Old Man" of British politics, conscience of the age) to the cause of Home Rule. In 1886 a Liberal government with Irish support introduced an Irish Home Rule Bill.

The Liberal Party split on the issue, the Bill was defeated and the Government fell – but Gladstone would find thereafter, should he care to visit, his portrait in many an Irish peasant cabin, in unlikely company with Parnell and the Pope. Gladstone's Liberals and Parnell's nationalists maintained their alliance: the election due in 1892 would return Gladstone to power: Home Rule seemed guaranteed.

Downfall – But Home Rule was not to be. A member of the Irish Party sued for divorce from his wife, Katherine O'Shea, naming in the courts Parnell as "co-respondent". Irish respectability was astonished to discover that Parnell had been in a relationship with Mrs O'Shea – known to history, derogatively, as "Kitty" – for many years and had fathered three children of her.

The vaunted unity of the Irish Party disintegrated – overnight. His colleagues disowned him. The Press denounced him. The Catholic hierarchy thundered against him, declaring:

Against these odds, he still campaigned. That year was 1890. He died the next, after grievous defeats at the polls.

His downfall echoed in Ireland for years afterwards. Christmas dinner in the opening chapter of Joyce's Portrait centres on a family bitterly disputing his memory. In his essay, The Shade of Parnell, 1912, Joyce wrote:

His monument in Dublin bears his life's legend: "No man has the right to fix the boundary to the march of a nation."